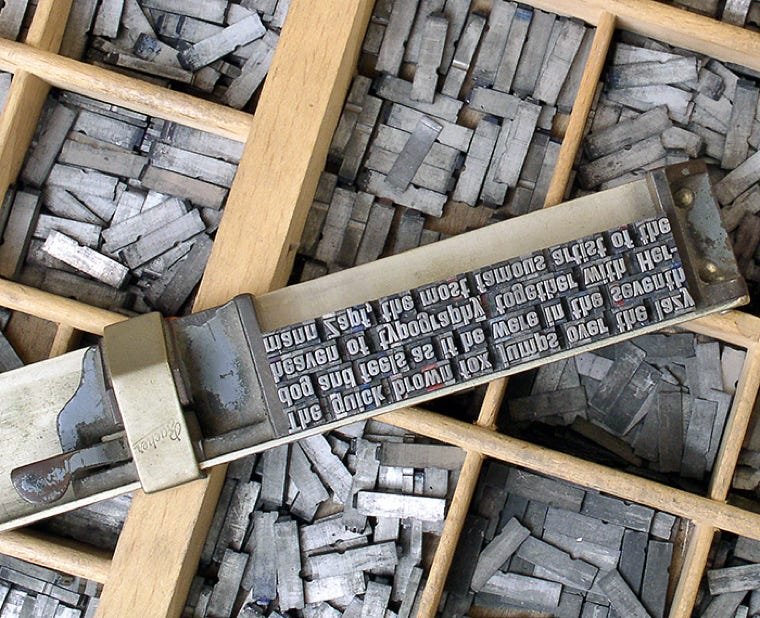

Type Case

Metal type glyphs: caps stored in the top, small letters in the bottom

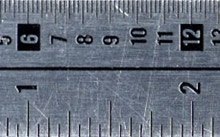

Pica Ruler

1 inch = 6 picas = 72 points

Line (Rule) Weights

from top to bottom:

1, 2, 3, and 4-point rules

Point Size

is a measurement that would include room for all the caps, ascenders and descenders.

Point Size

left: Times; right: Helvetica

Both are the same point size.

This one is set solid, 27/27.

This represents the point size

and the leading and is read as

“27 over 27”.

This one is set 24/28.

This one is set 24/20.

With photoset or digital type,

we can have lines of type that overlap into another line’s

space, as shown above.

Entire site and content © Copyright 2023 Kerry Scott Jenkins. All rights reserved.